Chronology of humane progress in India (Part Two)

Special: Chronology of humane progress in India

by Merritt Clifton, Editor, Animal People News

PREFACE:

The “Chronology of Humane Progress in India” covers only events originating before 2007, to give more recent events time to settle into perspective. The outcomes of court cases in which judgements were rendered more recently are discussed in light of antecedents which have evolved for much longer…”

Chronology part 2: 1910 to Project Tiger

(continued)

1910-1947 – Indian organizations were represented at the first International Humane Congress, held in Washington D.C. in 1910, and at the six ensuing International Humane Congresses, convened at sporadic intervals in London, Helsingborg, Copenhagen, Philadelphia, Brussels, and Vienna.

1924 – Hoping to win support from the League of Nations, French author Andre Géraud produced “A Declaration of Animal Rights,” a document which in 1926 inspired an “International Animals Charter” drafted by Florence Barkers. Attempts to create a declaration of animals’ rights in English that might be endorsed by the League of Nations apparently began with a 9-point “Animals’ Charter” authored at an unknown date by Stephen Coleridge (1854-1936), the longtime president of the British National Anti-Vivisection Society. The Coleridge edition was then expanded into “An Animals’ Bill of Rights” by Geoffrey Hodson (1886-1983), who was president of the Council of Combined Animal Welfare Organizations of New Zealand.

Hodson‘s version was amplified by the American Anti-Vivisection Society. After World War II, when the United Nations military alliance formed to fight the Nazis and other Axis powers was reorganized as the United Nations world assembly, incorporating the remnant programs of the League of Nations, efforts resumed to translate a theory of animal rights into global law.

The early participants included 13 organizations based in Britain, all long since merged into others or defunct; nine from India, mostly still existing; and two each, mostly vanished, from Sri Lanka, Germany, Austria, and Japan.

The U.S. was represented by the multinational World University Roundtable and the Western Federation of Animal Crusaders. The latter has at least two small regional descendants. A retired Presbyterian minister, the Reverend W.J. Piggott, in 1953 published in India an “Appeal for the International Animals’ Charter,” apparently based on the Barkers charter. “Between 1953 and 1956 a number of other preliminary charters were drawn up by the World Federation for Animal Protection Associations,” recalled Jean-Claude Nouett in a 1998 volume entitled The Universal Declaration of Animal Rights: Comments and Intentions, published by the Ligue Francaise des Droits de l’Animal.

Nouett was instrumental in advancing efforts to win United Nations Educational & Scientific Organization endorsement of a charter on behalf of animals, 1977-1989. The Treaty of Rome member nations ratified an updated version of the treaty in October 1997, taking effect in May 1999, which through the efforts of the Eurogroup Committee on Animal Welfare included an official “Protocol on Animal Welfare.” The World Society for the Protection of Animals took the lead in advancing the much revised document now known as the “Universal Declaration on Animal Welfare” in June 2000.

The 169-nation World Organization for Animal Health (Office International des Epizooties) on May 25, 2007 ratified the present edition of the Universal Declaration, including recognition of animals’ sentience. If approved by the U.N., the Universal Declaration would become international law. OIE ratification is regarded as a critical preliminary to placing the declaration before the U.N., which has not yet reviewed any of the drafts.

1926 – Mohandas Gandhi in October 1926 authorized a wealthy Ahmedabad mill owner to kill about 60 dogs who were roaming the mill premises. The Ahmedabad Humanitarian League objected. Gandhi responded with a series of eight long articles published in his weekly newspaper Young India between October and December 1926, which essentially restated the then prevailing attitude toward dogs in Britain, and recommended to India the policies adopted by Britain in the Dog Act of 1910. “Erring mortals as we are,” Gandhi wrote in the October 21 edition, “there is no course open to us but the destruction of rabid dogs…It is a thousand pities that the questions of stray dogs, etc. assume such a monstrous proportion in this sacred land of ahimsa. It is my firm conviction that we are propagating himsa in the name of ahimsa owing to our deep ignorance of this great principle…It is a sin, it should be a sin to feed stray dogs, and we should save numerous dogs if we had legislation making every stray dog liable to be shot…. Humanity is a noble attribute of the soul. It is not exhausted with saving a few dogs. Such saving may even be sinful.”

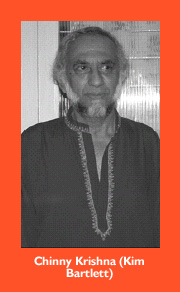

Continuing on October 28, Gandhi wrote, “The multiplication of dogs is unnecessary. A roving dog without an owner is a danger to society and a swarm of them is a menace to its (society’s) very existence…But can we take individual charge of these roving dogs? And if we cannot, can we have a pinjarapole for them? If both these things are impossible, there seems to be no alternative except to kill them…I am, therefore, strongly of opinion that, if we would practise the religion of humanity, we should have a law making it obligatory on those who would have dogs to keep them under guard, and not allow them to stray, and making all stray dogs liable to be destroyed after a certain date.” Gandhi in the Young India edition of November 4, 1928 reiterated, “Every unlicensed dog should be caught by the police and immediately handed over to the Mahajan if they have adequate provision for the maintenance of these dogs and would submit to municipal supervision as to the adequacy of such provision. Failing such provision, all stray dogs should be shot. This, in my opinion, is the most humanitarian method of dealing with the dog nuisance which everybody feels but nobody cares or dares to tackle. This laissez faire is quite in keeping with the atmosphere of general public indifference. But such indifference is itself himsa, and a votary of ahimsa cannot afford to neglect or shirk questions, be they ever so trifling, if these demand a solution in terms of ahimsa.” Commented longtime Blue Cross of India chief executive Chinny Krishna in 2009, “While the quotes from Gandhiji made in 1926 and 1929 are correct, I have it on the authority of Mr. V. Kalayanam, who was Gandhiji’s personal secretary for many years until Gandhiji was assassinated, that Gandhiji changed his mind a few years after these statements were made.”

In contrast to these well-documented statements, the most often cited pro-animal statement attributed to Mohandas Gandhi has never been adequately sourced: “The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated.” The one available reference, provided by Jon Wynne-Tyson in The Extended Circle (1985), is to “The Moral Basis of Vegetarianism,” but Gandhi used this same title for countless different lectures, pamphlets and newspaper and magazine essays during the last half century of his life.

1929 – Formation of the All India SPCA, the first known attempt to create an organization representing the Indian humane movement in the manner of the Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organizations. Founded at a conference in Delhi, the All India SPCA was housed in Calcutta by the Calcutta SPCA, and remained active at least until 1935.

1930 – The Royal SPCA of Great Britain experimented with electrocuting animals from approximately 1885 until about 1928, before concluding that it could never be considered acceptably humane by British standards. The RSPCA then exported the six Royal SPCA electrocution machines to India during a rabies panic. Dogs were legally electrocuted in India until the last of these machines known to remain in India was dismantled in 1997. Dogs continued to be illegally electrocuted in the city of Visakhapatnam until 1998, when the Visakha SPCA won the city pound contract, halted the electrocutions immediately, and instituted an animal birth control program which had eradicated rabies within the city and had almost eliminated rabies from the surrounding Visakhapatnam Circle as well by June 2010. Then a newly elected Greater Visakhapatnam Municipal Corporation government took responsibility for operating the local Animal Birth Control program away from the Visakha SPCA. The Visakhapatnam street dog population reportedly increased from about 7,000 to as many as 10,000 within the next year, and rabies returned to the city.

1933 – Bhagat Ram, secretary of the Animals’ Friend Society in Ludhiana, authored a resume of Indian animal welfare issues for The National Humane Review which remained largely current more than 75 years later. Published monthly by the American Humane Association from 1913 through 1976, The National Humane Review included frequent updates about humane work in India throughout the editorial tenure of Richard Craven, 1924-1939. Ram may have been the major Indian correspondent. Craven gave up The National Humane Review editorship to found the AHA Hollywood office, which monitors screen productions through contractual arrangements with the major unions representing screen actors. Craven continued to write for The National Humane Review, but coverage of India all but ceased.

1934 – Approximate date of the construction of the Koramangala dog shelter near the British barracks in Bangalore. Originally built as a holding facility for dogs who were to be electrocuted, and used as such for more than 60 years before being converted into an Animal Birth Control program surgical facility, the low-roofed Koramangala kennels house hundreds of dogs with very little barking. The unusual quiet of the Koramangala pound may result mostly from the kennels being arranged in single rows, with each front facing the back of another kennel instead of the front of another kennel and an unfamiliar dog staring back. By tradition, the dogs are housed in compatible pairs whenever possible.

1934 – The National Humane Review in November 1934 described the unsuccessful efforts of 32 humane societies from all over India to try to stop the sacrifice of 1,000 goats, 16 buffalo, and 1,600 birds at Ellore, in response to a smallpox outbreak. The leaders of the anti-sacrifice campaign were said to be the Bombay Humanitarian League and the Madras SPCA.

1938 – The National Humane Review in July 1938 reported that a Miss Howard Rice, of Pune, had extensively documented the cruelty of the Indian monkey export trade. A separate article on the same page described the operations of the Madras SPCA, whose patrons were identified as Lord Erskine, the Governor of Madras, and his wife. “The society last year secured 2,902 convictions of persons on whom advice and warning proved ineffective,” reported The National Humane Review. “Of the animals involved, 2,060 were bullocks and 527 were ponies. The society prosecuted 85 cases of starvation of calves. It is gratifying to learn,” The National Humane Review continued, “that no serious case of animal sacrifice was reported. Stray dogs are a problem in India, as in our own country,” the editors added, “and city handling in India is as revolting as in many American cities. Through the endeavors of the Madras SPCA, electrocution has taken the place of clubbing dogs to death, and in 1936 dogs were conveyed by motor van to the lethal chamber, but the city vans have been put in storage and the old system of dragging dogs through the streets by means of strings has been restored. The city’s excuse is lack of funds. That the practices of city dog catchers are much the same the world over is indicated by a complaint that the dog catchers were taking only healthy dogs and passing up the diseased ones. The branches [of the Madras SPCA] report separately,” the article concluded. “The Trichinopoly branch reports 3,066 prosecutions; Calicut 1,061; Tanjore 738; Vellore 225; Salem 791; and Coimbatore 3,682.”

1940 – The August 1940 edition of The National Humane Review reported that, “The Arab University of El Azhar, Cairo, has at last issued an order about a request of an Indian Prince asking for replies to these three questions: 1) Is a Mussulman allowed to have a watchdog for his property? 2) Is he allowed to play with a dog? 3) If a dog touches part of the body and clothing of a Mussulman who has just prayed, is the man considered as impure and his prayers nullified? In a long document, the answers of the Arab University are that the dog is not an impure animal, but, on the contrary, is by his kind of life, a friend of the Mussulman, and that the latter is allowed to keep it at home and to play with it, and that, even if he is touched by a dog, he remains pure and his prayers are not nullified.”

1946 – The first report from India to reach the National Humane Review in seven years mentioned that the Animals’ Friends Society in Ludhiana was distributing a pamphlet biography of American SPCA founder Henry Bergh.

1947 – Jawaharal Nehru wrote into the constitution of India as Article 51-A[g] that “It shall be the fundamental duty of every citizen of India to protect and improve the Natural Environment including forests, lakes, rivers and wildlife, and to have compassion for all living creatures.” This was reinforced by the 1960 Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act.

1947 – Passage of the first national regulations governing gaushalas, gosadans, and pinjarapoles. The terms “gaushala,” “gosadan,” and “pinjarapole” are often applied interchangeably to cow shelters, and often refer to the same facility, but under the national regulations they have somewhat different legal definitions. “Gaushalas” have an awkward dual mandate, being officially considered agricultural institutions, as well as having an animal welfare role. Gaushalas often breed cattle, ostensibly to conserve native genetic traits. Many have become commercial dairies. “Gosadans” are hospices for dying cattle. “Pinjarapole” seems to be the most inclusive term for cow shelters of any type.

1947 – The National Humane Review in October 1947 mentions that humane societies in Calcutta, Coonoor, Nilgiris, Madras, and Delhi are attempting to rebuild and regain momentum lost during years of global and national conflict. The National Humane Review was published for another 30 years, but this item appears to have ended attempts to provide Indian coverage.

1953 – Indian legislator Rukmini Devi Arundale, famed earlier in life as a classical dancer, introduced the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Bill in the Rajya Saba (upper house of Parliament) as a private member’s bill. “It passed in 1960 after an identical bill was introduced by Nehru’s government and Rukmini Devi magnanimously agreed to withdraw hers,” recalled longtime Blue Cross of India chair Chinny Krishna. Arundale later “served as first chair of the Animal Welfare Board of India, created by the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, and remained chair for most of the time from 1962 until her death in 1986,” at age 82, “except for a brief period after the Emergency in 1975,” according to Krishna. “She turned down the Presidency of India when offered it by Morarji Desai, the Prime Minister of India after the Congress Party was voted out of power in 1977 for the first time since independence. Mrs. Arundale was a strong supporter of the Blue Cross’ early spay/neuter work for street dogs,” begun in 1964.

1954 – Update of the national regulations governing gaushalas, gosadans, and pinjarapoles.

1954 – Formation of the Nilgiris Animal Welfare Society by British immigrant Dorothy Dean, who died in 1976. After several stormy transitions of British, American, and local leadership in the mid-1990s, the American faction in 1998 formed the India Project for Animals and Nature. The U.S. faction withdrew from India circa 2000. IPAN has stabilized and re-emerged as a leader in Indian humane work under Nigel and Ilona Otter.

1956 – Founding of the Jain Bird Hospital in Delhi. The hospital has separate wards for sparrows, parrots, domestic fowl, and pigeons, but does not treat birds of prey.

1959 –

Formation of the Blue Cross of India by [Capt.] V. Sundaram and Usha Sundaram, at their home in Chennai. Taught to fly at age 20 by her husband, V. Sundaram, who was among the first pilots for Tata Airways, Usha Sundaram initially flew the VT-AXX that was personal aircraft of the Maharaja of Mysore, Jayachamaraja Wodeyar Bahadur, a noted patron of music. From 1945 to 1951 the Sundarams were pilots for the first Indian prime minister, Pandit Jawarharlal Nehru. After Usha Sundaram became the first graduate of the Indian government flight training school in Bangalore in 1949, she continued alone as Nehru’s pilot while her husband devoted more of his time to airline business.

_____________________

Captain Sundaram, born on April 22nd, 1916, had always wanted to care for animals. In his own words, “God had given me so much that I thought I ought to do something in return. There are so many charitable institutions for human beings, but so few for animals. “With full fledged support from his family (his wife Usha and the children built the first few kennels with their own hands), he was soon rescuing and sheltering animals in his T Nagar residence till 1968, when Blue Cross was shifted to its own premises at Adyar.

_____________________

After they cofounded the Blue Cross, their son Chinny Krishna, then 15, participated in animal care and rescue for the first several years, then earned an engineering degree in the U.S. Upon his return to India in 1964, the Blue Cross was formally incorporated, with the Sundarams, Chinny Krishna, and his bride Nanditha Krishna among the founding trustees. In 1966, Chinny Krishna began developing the prototype for the Animal Birth Control program that became Indian national policy in 1997, funded by the Indian government since 2003. Usha Sundaram continued as a Blue Cross volunteer in various capacities until her death in April 2010. The Blue Cross of India now has four animal hospital and shelter complexes in the Chennai area. The Blue Cross of Hyderabad, begun in 1992 by actress Amala Akkineni, is not an affiliate, but was named in honor of the Blue Cross of India. The Blue Cross organizations work closely together.

1959 – Crystal Rogers founded the Animals’ Friend shelter in Delhi.

Emigrating to India with her parents at age six in 1912, Rogers did animal rescue on the side as a mobile canteen driver with the Gurkha Regiment in World War II. Rogers later founded Help In Suffering, in Jaipur, directing the first Help In Suffering clinic and shelter from 1978 to 1991, and then at age 85 founded Compassion Unlimited Plus Action in Bangalore. Among the young volunteers and visitors Rogers influenced were Maneka Gandhi, founder of People for Animals; Anuradha Modi, leader of Kindness to Animals and Respect for Environment; Amala Akkineni, founder of the Blue Cross of Hyderabad; and Suparna Ganguly, Sheila Rao, and Sanober Bharucha, her eventual successors at CUPA. Rogers died in 1996.

1959 – Billy Arjan Singh founded Tiger Haven, a private preserve that eventually became Dudhwa National Park. Born into the Ahluwalia royal family of Kapurthala, Singh shot seven tigers as a youth, but came to detest hunting as he saw tigers, leopards, blackbuck, and other Indian “trophy” animals shot to the verge of extinction. After starting Tiger Haven, Singh notoriously dragged poachers to town behind his jeep and expressed unsympathetic views about the losses of employees and visitors who brought their children into proximity with the captive tigers and leopards he rehabilitated for release and bred with former zoo stock. One of his animals was Tara, a part Siberian tiger he imported from England in 1976, dismissing objections that he was “contaminating” the Indian tiger gene pool. A recluse, whose closest companion for many years was his elephant, Singh preserved wildlife at the cost of antagonizing so many people that elected officials came to treat him as a public enemy.

Backlash against Singh’s methods, as well as flagrant official corruption, nearly ruined the Indian refuge system in the late 20th century, under the mantra of “sustainable use.” The theory was that ordinary Indians would support refuges only if the refuges contributed to their prosperity. Refuges were opened to grazing, wood-gathering, and eventually to so much other economic activity that some, like Sariska, were reduced to heavily trafficked tourist corridors, losing the wildlife that they were founded to protect. Valmik Thapar, an initially reluctant student of Singh’s, redeemed Singh and the refuge concept by demonstrating with Singh’s help and investment how habitat reclamation could provide even greater economic benefits than the other common uses of refuge land. Singh, 92, died at Tiger Haven on January 1, 2010.

1961 – The World Wildlife Fund was founded by trophy hunter Sir Peter Scott and cronies, among them captive bird-shooters Prince Philip of Britain and Prince Bernhardt of The Netherlands, the whaler Aristotle Onassis, and then-National Rifle Association president C.R. “Pink” Gutermuth. A primary goal of WWF was to promote funding of wildlife conservation internationally by sales of hunting permits, as the National Wildlife Federation had already achieved in the U.S. This, it was hoped, would prevent newly independent former colonies of European nations from following India and Kenya in banning sport hunting (which was not finally accomplished in either India or Kenya until 1977, although attempts began much earlier). WWF-India, operating semi-autonomously, debuted in 1969.

1962 – Formation of the Animal Welfare Board of India. Headquartered in Chennai, the AWBI is a statutory advisory board to the government of India, whose founding chair was Rukmini Devi Arundale. The official mandate of the AWBI is:

a) To keep the law in force in India for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals under constant study and to advise the government on the amendments to be undertaken in any such law from time to time.

b) To advise the Central Government on the making of rules under the Act with a view to preventing unnecessary pain or suffering to animals generally, and more particularly when they are being transported from one place to another or when they are used as performing animals or when they are kept in captivity or confinment.

c) To advise the Government or any local authority or other person on improvements in the design of vehicles so as to lessen the burden on draught animals.

d) To take all such steps as the Board may think fit for amelioration of animals by encouraging, or providing for the construction of sheds, water troughs and the like and by providing for veterinary assistance to animals.

e) To advise the Government or any local authority or other person in the design of slaughter houses or the maintenance of slaughter houses or in connection with slaughter of animals so that unnecessary pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is eliminated in the pre-slaughter stages as far as possible, and animals are killed, wherever necessary, in as humane a manner as possible.

f) To take all such steps as the Board may think fit to ensure that unwanted animals are destroyed by local authorities, whenever it is necessary to do so, either instantaneously or after being rendered insensible to pain or suffering.

g) To encourage by the grant of financial assistance or otherwise, the formation or establishment of pinjarapoles, rescue homes, animal shelters, sanctuaries and the like, where animals and birds may find a shelter when they have become old and useless or when they need protection.

h) To co-operate with, and co-ordinate the work of associations or bodies established for the purpose of preventing unnecessary pain or suffering to animals or for the protection of animals and birds.

i) To give financial assistance and other assistance to Animal Welfare Organisations functioning in any local area or to encourage the formation of Animal Welfare Organisations in any local area which shall work under the general supervision and guidance of the Board.

j) To advise the Government on matters relating to the medical care and attention which may be provided in animal hospitals, and to give financial and other assistance to animal hospitals whenever the Board think it is necessary to do so.

k) To impart education in relation to the humane treatment of animals and to encourage the formation of public opinion against the infliction of unnecessary pain or suffering to animals and for the promotion of animal welfare by means of lectures books, posters, cinematographic exhibitions and the like.

l) To advise the Government on any matter connected with animal welfare or the Prevention of infliction of unnecessary pain or suffering on animals.

1964 – Formation of the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals. Created by a 1964 act of the Indian Parliament, the CPCSEA by 1966 had produced a set of Rules for Animal Experimentation which came into legal force on October 4, 1968. However, the first appointees to the CPCSEA met just twice in four years. “During the next 27 years,” longtime Blue Cross of India chair and multi-time CPCSEA appointee Chinny Krishna (below) recalled in 2003, “the CPCSEA was ritually renominated by the Government of India, with the chair being always the head of the Indian Council of Medical Research, or an equally senior official of the Ministry of Health.

It too met precisely twice. Not one notice was issued to any lab for contravention of the rules. Not one inspection was made,” even though the Blue Cross of India and other organizations often exposed abuses that occurred within CPCSEA jurisdiction. The Indian National Science Academy separately produced a new set of research guidelines in 1992. Still, laboratories remained at liberty to do as they would until 1996, when then-Animal Welfare Board of India chair A.K. Chatterjee, a retired army general, managed to reconstitute the CPCSEA with Maneka Gandhi as chair and Chinny Krishna as a member, outnumbered by four heads of government research institutions. Under Mrs. Gandhi the CPCSEA began exercising independent regulatory authority. Experiments approved by the IAEC no longer won automatic CPCSEA approval. Of 467 laboratories visited by the CPCSEA during Mrs. Gandhi’s tenure, exactly 400 – 86% – failed to meet the basic animal housing and care requirements. Laboratories were cited a total of 590 times for deficiencies in animal care. Mrs. Gandhi was forced out of the CPCSEA chair on July 2, 2003, when she was dropped from the Indian federal cabinet entirely as result of concerted opposition from both the Indian biotech industry and practitioners of animal sacrifice.

It too met precisely twice. Not one notice was issued to any lab for contravention of the rules. Not one inspection was made,” even though the Blue Cross of India and other organizations often exposed abuses that occurred within CPCSEA jurisdiction. The Indian National Science Academy separately produced a new set of research guidelines in 1992. Still, laboratories remained at liberty to do as they would until 1996, when then-Animal Welfare Board of India chair A.K. Chatterjee, a retired army general, managed to reconstitute the CPCSEA with Maneka Gandhi as chair and Chinny Krishna as a member, outnumbered by four heads of government research institutions. Under Mrs. Gandhi the CPCSEA began exercising independent regulatory authority. Experiments approved by the IAEC no longer won automatic CPCSEA approval. Of 467 laboratories visited by the CPCSEA during Mrs. Gandhi’s tenure, exactly 400 – 86% – failed to meet the basic animal housing and care requirements. Laboratories were cited a total of 590 times for deficiencies in animal care. Mrs. Gandhi was forced out of the CPCSEA chair on July 2, 2003, when she was dropped from the Indian federal cabinet entirely as result of concerted opposition from both the Indian biotech industry and practitioners of animal sacrifice.

1972 – Passage of the Wild Life Protection Act.

1972 – Opening of the 625-acre Indira Gandhi Zoological Park in Visakhapatnam, the first Indian zoo to be built to what was then considered to be a state-of-the-art design. Actually operating the zoo to world class standards proved to be much more difficult that constructing it, but after more than 30 years of struggle, the zoo appears to have stabilized, and in 2001 became home of one of the first Animal Rescue Centres accredited by the Central Zoo Authority.

1972 – The first formal all-India tiger survey found that the national population of tigers had fallen from an estimated 45,000 in 1900 to just 1,827. The tiger population continued dropping, to as few as 1,200. Organized in late 1972, Project Tiger debuted in April 1973.

Sponsored primarily by the World Wildlife Fund, Project Tiger was credited with doubling wild tiger numbers during the next 25 years, through a variety of conservation schemes at 40 designated Project Tiger reserves.

In 2005, however, investigators belatedly realized that tigers had been extirpated entirely from Sariska, one of the most celebrated Project Tiger locations. Several other Project Tiger sites appeared to have either no tigers or no breeding pairs.

The National Tiger Conservation Authority reported in 2008 that the Indian tiger count had dipped to as few as 1,411, plus uncounted tigers who range back and forth across the Bangladesh border in the Sunderbans. Long touted as the major Indian conservation success, Project Tiger is now widely regarded as one of the world’s most notorious conservation boondoggles, since the organizational structure encouraged corrupt managers to inflate tiger counts to receive more funding. The government of India has significantly increased allocations for protecting tigers against poaching and relocating tribal people and their animals out of tiger sanctuaries. Meanwhile, programs modeled on Project Tiger have been proposed to benefit Indian elephants, Asiatic lions, and cheetahs.

___________